Two-Shots in Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Well, I’m still hard at work breaking down Twilight Breaking Dawn Parts 1 and 2. It’s the end of the semester, so I haven’t had as much time to finish up my write-ups, but hopefully you’ll see them soon.

So as a follow-up to my look at close-ups in Barry Jenkins’ If Beale Street Could Talk, I thought I’d share the second-half of my Directing course discussions, by looking at the use of two-shots in Celine Sciamma’s gorgeous and amazing Portrait of a Lady on Fire.

Two-shots are sort of the under-appreciated work horse of cinema. A lot of filmmakers seem to settle for pretty standard two-shots, often because they are just establishing shots used before moving into closer views. Generally these find characters either facing each other:

Or shoulder to shoulder:

Additionally, the most frequently used two-shot is actually the over-the-shoulder shot (OTS). On its own, one OTS shot is not a great two-shot.

A closed-off OTS only shows the face of one character, and the back of the other:

A more open OTS can show the faces of both characters, though generally one is more in profile:

This is why the OTS is the most common shot in the shot/reverse shot series, which in essence stitches two shots together to create a “complete” two shot.

However, in the hands of a creative director, the two-shot can be an aesthetically beautiful, well-composed shot in its own right. And plenty of filmmakers have created wonderful two-shots. But it’s not often that an entire movie is built almost entirely around two-shots in the way that Celine Sciamma does with Portrait of a Lady on Fire. In fact, there are few over the shoulder shots in Portrait, and when there are, they rarely fall into a predictable shot reverse shot series. Why are two-shots so important in Portrait? It’s pretty straight-forward—it’s a romance and showing the characters together in two shots is more important than showing them in single or close-up shots. Of course, there are plenty of single shots, especially earlier in the movie before the romance forms, and later, in a key scene where the two protagonists Marianne (Noemie Merlant) and Helene (Adele Haenel) have an argument.

So let’s take a look at some of the gorgeous two-shots of Portrait of a Lady on Fire:

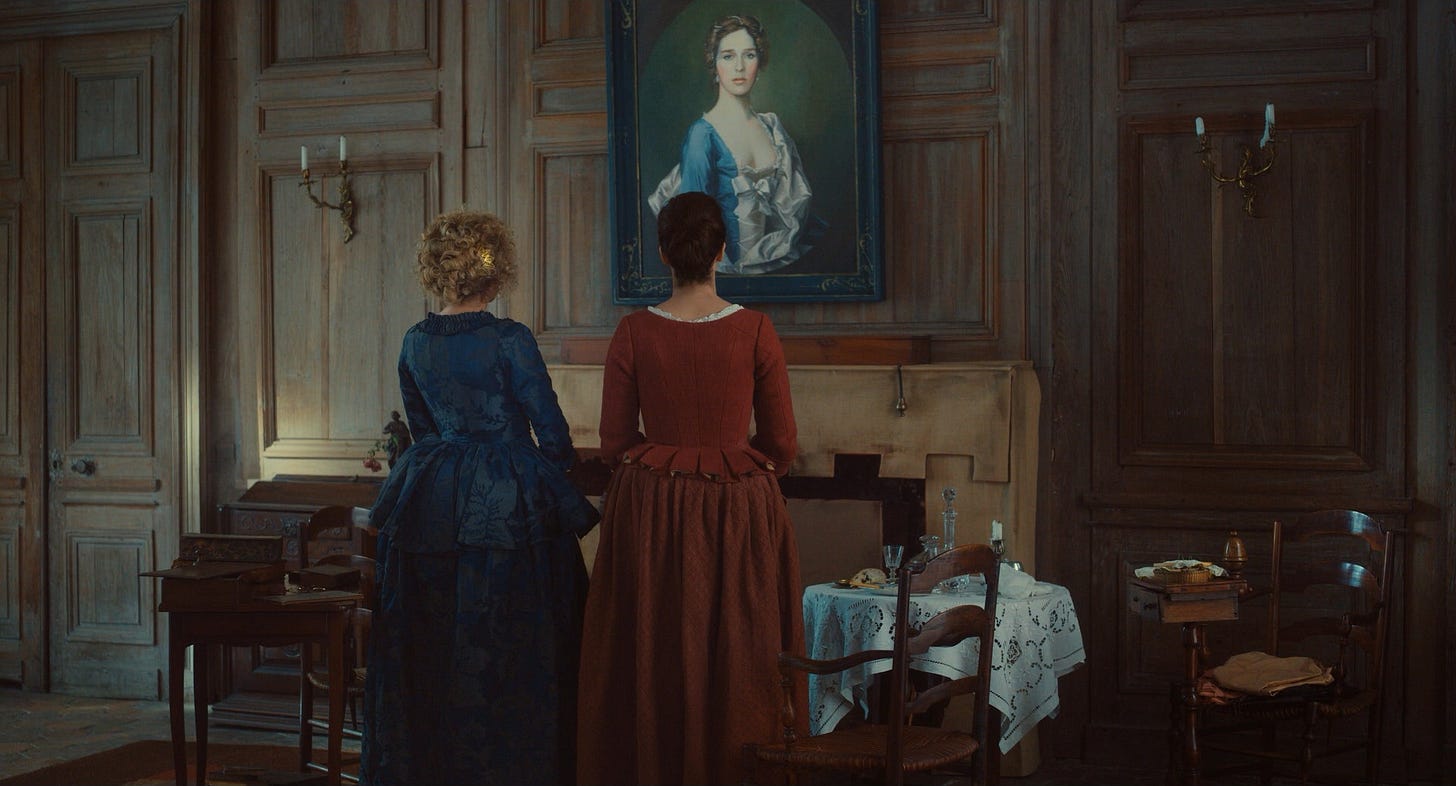

The film starts with a stacked two-shot of two art students which will foreshadow the first two-shot of Marianne and Helene:

Early two-shots in the movie are similar to two-shots we’re often used to seeing in movies, including shoulder to shoulder, facing, and over the shoulder shots:

Our first two-shot of Marianne and Helene is a cleverly disguised shot, that initially only shows Marianne, before revealing Helene, their faces merged, foreshadowing their future romance.

The next few two-shots of Marianne and Helen are less intimate, as the two characters are still feeling each other out, and one keeps a secret from the other (that Marianne has been hired to superstitiously paint a wedding portrait of Helene, who refuses to sit for one because she doesn't want to marry).

The beach becomes a key place for bonding between the two characters, but early on they sit farther apart or are subtly angled away from each other:

Finally, in a key scene, Marianne describes orchestral music to Helene (who has only heard the organ at church), and plays pieces of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, creating the first true bond between them. As we see in the next four frames, the two-shots become more and more intimate as the scene progresses. In fact, there are no singles or close-ups in the scene:

At the end of the Vivaldi scene, however, Marianne tries to comfort Helene over her upcoming nuptials, but the attempt backfires, and later on the two-shots are framed as frontal OTS shots, separating the two women.

Despite their momentary misunderstanding, the next time we see them on the beach, they are closer and angled toward one another, in a more intimate pose than we have seen in previous scenes on the beach:

Of course, there are other characters in the story, and in a key scene Helene agrees to sit for a portrait, but her mother will be departing for the week. Though both shots are somewhat standard, Helene’s caress of her mother shows how much subtle blocking and posing can turn a standard two-shot into something special:

Once Helene begins to sit for Marianne, the initial interaction is awkward and forced as Marianne positions Helene:

From here, the two-shots become more interestingly framed:

And the next time Helene sits for Marianne, their positioning is more intimate and sensual:

And finally, in an almost perfect combination of costuming, blocking, and posing Sciamma uses a standard facing two-shot to finally have Marianne and Helene kiss for the first time. Note how clearly we can see both characters’ faces (once they remove their scarves):

It’s worth noting that in many kissing scenes, character are shot over the shoulder, or even more shockingly one character’s hand covers the camera facing side of the other character (this is often standard in heterosexual kissing scenes where the man’s hand almost completely covers the woman’s face). The result, either way, is that one or both of the characters’ faces are completely blocked, taking away the intimacy of the moment:

In the next kissing scene between Marianne and Helene, we start in a longer wide shot, before Marianne turns, then leans her head back to kiss Helene. Even with Helene’s hand prominent in the shot, Marianne’s face is clearly visible:

In the final shot of the series, Marianne turns the rest of the way around, and we get a beautiful pose where each character buries her head in the crook of the neck of the other, reflecting the melancholy of a relationship that they (and we) know won’t last.

In an important subplot, the servant in Helene’s home, Sophie chooses to have an abortion. We initially see the difficulty Marianne and Helene have watching, but Sciamma turns the moment into one of grace and understanding as Sophie lays next to an infant during the procedure:

In an earlier scene, Marianne has told Helene that she is not allowed to paint nude men because then she will be unable to paint the most important subjects (not being familiar with male anatomy). So that night, Helene decides that Marianne should paint the moment of the abortion, redefining what important subject matters are, and that they don’t have to involve men:

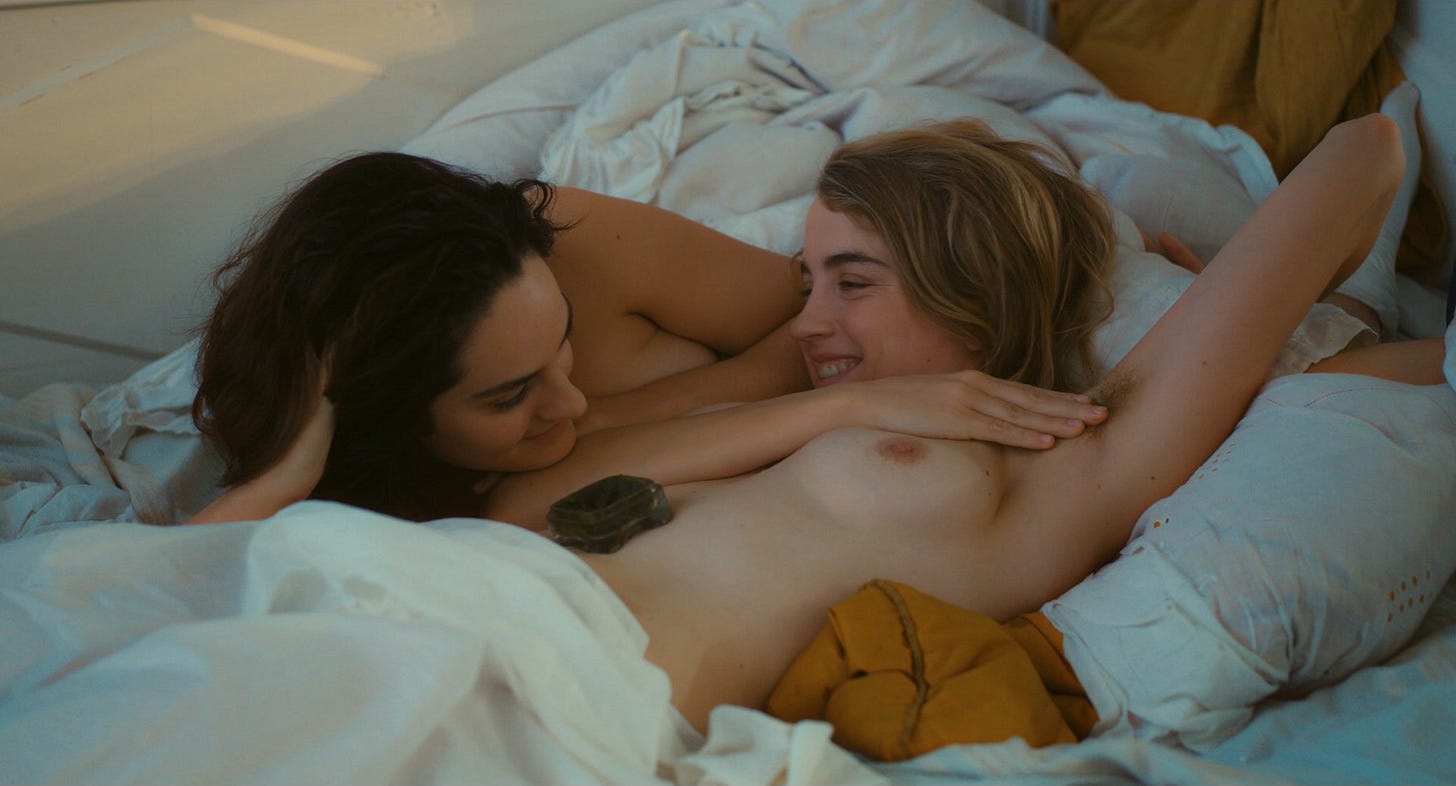

Afterwards, with their love affair in full blossom, Marianne and Helene are portrayed by Sciamma in a variety of two-shots, some familiar, others unique in their posing and intimacy:

Finally, with Marianne and Helene’s time coming to an end, Sciamma poses their final scene on the beach in a two-shot that is an almost identical pose to the standing two-shot of their second kiss, but this time with the Marianne holding Helene, rather than the reverse:

On their final night together we see them in bed, the first shot being the only true overhead of the two, and the second recalling their opening two shot, in which their two faces are merged:

The next morning the two-shot transitions from a more intimate shot, to a less intimate one, as Marianne corsets Helena, literally tying a bow on the end of their relationship:

And finally, in their last two-shot together, Marianne grasps Helene and hugs her. In this moment, we are aligned with Marianne and their pose puts her face in front of Helene’s, and neither she, nor we, can see Helene’s face. Perhaps it is simply too painful:

In a contemporary cinema of small screens, the close-up has become king. At its best the close-up is unique in its power to show the emotional intimacy of a single character. But emotion almost always grows out of relationships, and in Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Celine Sciamma privileges the relationship of two women through her amazing use of the two-shot.