Phantom Thread

I apologize for how long it’s been since my last structure breakdown post! Between the holidays and prepping for a short film I was planning to shoot in early January, I’ve been quite busy. The shoot had to be postponed because I contracted Norovirus! But no worries, I am back to full health and am working on rescheduling the shoot.

In the meantime, I decided to do a breakdown of my favorite Paul Thomas Anderson film, Phantom Thread. With PTA’S most recent film One Battle After Another performing so well and on so many Top Ten Lists for 2025, and my choice to include Phantom Thread as a film in my Directing class for the spring, I thought this would be the perfect opportunity to analyze it. I love it’s style, narrative structure, and of course marvel at the performances of Daniel Day Lewis, Vicky Krieps, and Lesley Manville.

Phantom Thread is a challenging film to breakdown, as it is setup in many ways as a typical film with a strong-willed creative artists in Reynolds Woodcock, who is seemingly our protagonist with a fairly typical set of external and internal goals. But as the movie progresses it turns into something quite different.

As always, these breakdowns contain SPOILERS, and are only recommended if you've already seen the movie. You can check my introduction to these breakdowns, to get an overview of my process and philosophy.

Feel free to let me know what you think in the comments below!

The Basics

Director: Paul ThomasAnderson

Writers: Paul Thomas Anderson

Release Date: 2017

Runtime: 130 minutes

IMDB: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt5776858/?ref_=ext_shr_lnk

Movie Level Goals

Protagonist #1: Reynolds Woodcock

False External Goal: To continue his success as the head of a major fashion house

Relationship Goal: To find a worthy partner to fit into his life

SUCCESS | FAILURE | MIXED

Internal Goal: To give up control

Protagonist #2: Alma

External/Relationship: Develop a co-equal loving relationship with Woodcock

SUCCESS | FAILURE | MIXED

Internal Goal: None

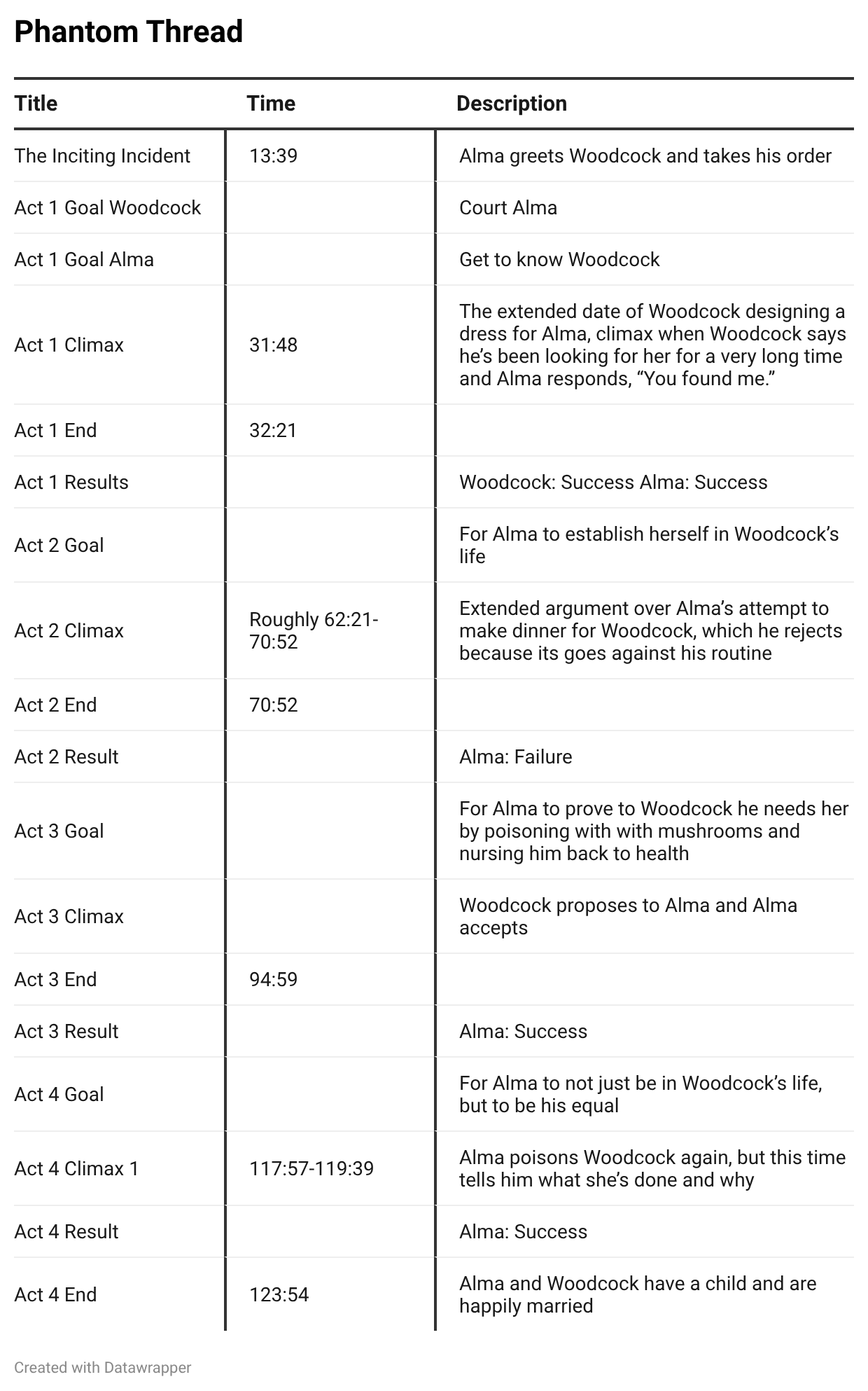

As is clear, the goal structure of Phantom Thread is complex and unique. You can see my explication of these complexities in the Three Observations below

Three Observations

Observation #1: The False External Goal

Paul Thomas Anderson starts off Phantom Thread quite cleverly, leadings us to believe we are getting a somewhat typical “Great Man” biography—in this case a profile of the fictional fashion designer Reynolds Woodcock (played with usual grace and depth by Daniel Day-Lewis).

The film starts with a typical day in Woodcock’s life as he dresses, grooms, eats breakfast, and interacts with his sister and business manager Cyril (Lesley Manville). We notice (though barely) that he has a girlfriend, whom he treats with disregard. He then welcomes a client, Countess Harding, for whom he has designed a bespoke dress for an upcoming occasion. Woodcock is everything we expect he might be: genius, precise, observant, prickly, demanding and imperious. The typical “great man” genius.

The initial scenes focusing on his fashion career leads the audience to believe that Woodcock’s external goal will involve in some way achievement as a fashion designer. However, things begin to veer off course when, in the inciting incident, Woodcock meets Alma (Vicky Krieps), a waitress at a local restaurant he sometimes frequents on his travels, this time while his car is being serviced. The attraction is immediate, and the rest of the act focuses on the development of their relationship. Woodcock brings Alma out to dinner after she has left him a very forward note, “For the hungry boy, my name is Alma.” After their dinner, Woodcock brings Alma back to his home and designs a dress for her in a very intimate yet awkward fashion, as he takes her measurements while she is wearing only a slip, with Cyril watching and taking down her measurements. Despite the awkwardness, and Woodcock’s seemingly derogatory comments about her measurements, Alma agrees to try on an already made dress, and the entire scene almost feels like the equivalent of a sex scene as Alma entrusts herself to Woodcock’s intimacy (there is never a sex scene in the movie—though both designing and eating often replace sex as intimate activities for Woodcock and Alma. And despite the extremely obvious double entendre of Woodcock’s name, we never come close to seeing Woodcock’s…). The act ends with Woodcock declaring he’s been looking for someone like Alma for a very long time, and Alma replying, “You found me.”

So is this a relationship movie or a “creative genius” movie or both? Act 2 continues to confuse the issue by focusing much of its attention on the preparation and execution of a fashion show at The House of Woodcock, and Reynold’s exhaustion afterward. Additionally, Woodcock designs a dress for an aging client, embarrassed by her weight gain and loss of beauty, and after appearing at function drunkenly wearing the dress, Alma and Reynolds demand the dress back, and literally strip it off the passed out body of Mrs. Rose. Yet, despite this focus on his work as a designer, neither situation creates the Act 2 structure or a goal to build it on. They are simply the backdrop for developments in the relationship between Reynolds and Alma. She is present throughout and it’s her goal that drives the act and motivates the climax. She wants to be a major part of Woodcock’s life. Initially, Alma slips into Woodcock’s routines, after some early stumbles. She learns to eat quietly at breakfast, and becomes both muse and model as well as a member of his design staff. However, she wants more and in the extended climax, she prepares a special dinner just for him, which he rejects, causing a heated argument between them. Reynolds doesn’t like surprises and resents the intrusion on his routine, while Alma believes his work obsession means it’s only a matter of time before she is discarded like so many of Woodcock’s previous amours.

By this point the direction of the film becomes clear—this is a relationship film, a romance, and despite occasional scenes focusing on his fashion work (specifically designing a wedding dress for a princess in Act 3) the movie is in no way structured around any goals involving Woodcock’s work as a designer (the wedding dress completion is interrupted by his illness, but its his staff who completes the dress, and the princess and the wedding itself largely drifts out of the story), and by the final act this work is barely present at all. Not only is Woodcock’s fashion work not the focal point of the movie’s structure, his goals don’t structure the movie at all (at least after Act 1), which leads us to our second observation:

Observation #2: The Split Protagonist

Though Reynold’s seems setup at as the protagonist because of our initial alignment with him at the start of Act 1, I was somewhat misleading on Observation #1. The movie doesn’t actually start with Reynolds—rather it starts with a brief scene with Alma talking to Woodcock’s doctor in the future about their relationship. She is actually introduced first, and as we watch Act 1 unfold we can easily see the inciting incident and the Act 1 Climax from both Woodcock and Alma’s perspective. Because we are more aligned with Woodcock leading up to the Inciting Incident, we may be more likely to observe the goals from his perspective. But as the movie progresses we become more and more aligned with Alma, and from the start of Act 2 on, it is her goals that structure the rest of the movie. In Act 2, she wants to become a more important part of Woodcock’s life. This backfires spectacularly in the Act 2 climax, when Reynolds rejects Alma’s carefully planned dinner date, and it seems their relationship is close to dissolving. But Alma is not so fragile. In Act 3, her goal is to prove to Woodcock that he needs her, and she does so in startling fashion—she gives him tea brewed with poisoned mushroom, which makes him violently ill. Alma blocks Cyril and a doctor from caring for Woodcock and takes on the job herself. By the end of the act, she has proved her worth, and Woodcock proposes. Unfortunately, the job is not yet done. Though Woodcock initially appreciates the need for change, he begins to resent Alma’s presence and influence and complains to Cyril that Alma is in essence ruining his life and his work. Alma can’t just prove she belongs in Woodcock’s life—she must prove she is his equal and that he must accept her entirely for who she is. So she poisons him again, this time letting him know it as soon as she does, and tells him he must fully submit to her care and be open to her, and then she will make him strong again to continue his work. In the moment, he finally appreciates her strength of will and her equal standing and declares in one of the great cinematic lines, “Kiss me girl before I’m sick.”

So if the movie is structured around the external goals of Alma, doesn't that make her the protagonist of the movie? In some ways yes, but protagonists are sometimes complicated business. One of our other expectations for protagonists is that they have an internal goal which provides meaning and growth. But Alma has no internal goal. One might argue that she must grow the strength to be Woodcock’s equal, but the movie never suggests that she is not initially his equal—only that he doesn’t recognize it. Alma never changes, never grows—she is a constant. Though she provides the external goals and structure, it is Woodcock who is forced to grow and change. The initial implied external goal involving fashion is replaced by the relationship goal of finding and recognizing the partner who can fit his life (see Observation #3). More importantly, he has the internal goal—he is the one who must grow and who provides meaning for the film. Woodcock must surrender control and understand that for a woman to truly fit into his life in a fulfilling way, he must treat her as an equal, rather than maintain absolute control of everyone and everything around him.

The result is a split protagonist with Alma providing the main external goals that structure the movie and Reynolds providing the internal goal that creates change, meaning, and emotional investment.

Observation #3: The Mixed Ending and Goal Connections

Because Alma only has an external relationship goal, her ending is quite clear and easy to understand. After poisoning Woodcock for a second time and getting him to finally see and understand who she is and how she must fit into his life, she succeeds at her goal. She doesn’t need to change, and since she only has one goal, there isn’t an internal goal that depends on success of the external goal (or vice versa).

However, for Reynolds the goals are more complicated. Obviously, by the mid-point of the movie it is clear that any external goal for Woodcock is not based in his work as a designer. This is a relationship movie and success or failure externally depends on whether he successfully achieves the relationship he wants. Note that in the goal list above I write his relationship goal as being both Successful and Mixed. Clearly he doesn’t fail—he ends up with Alma and is happy and settled. But his goal of a successful relationship is not what he had envisioned. For most of the movie Reynolds wants Alma to slip seamlessly into his life. He wants no change at all. When he wants quiet, he wants quiet. When he wants to work, he wants to work. They should go out when he wants to go out. They must eat food prepared how he likes it prepared. This is his relationship goal. But, of course, this will never work, especially because he also at some level knows he wants a woman like Alma—someone who can be his equal. And the only way for him to get this is to understand and succeed at the internal goal—he must be willing to give up control in order to have a successful, fulfilling relationship with Alma. For Reynolds, success at the internal goal leads to success for his relationship/external goal. But even then, he must change his assumptions for what a successful relationship will look like. So he succeeds, but his success is somewhat mixed, as he doesn’t get what he thinks he wants but instead gets what he actually needs: a relationship based on mutual appreciation and equality.