Ocean's 11 Structure Breakdown

The Intro

A week or so ago, I had a great time with my partners in crime at Podcast 241, analyzing Ocean’s 11. So checkout the podcast and read my breakdown below!

As always, these breakdowns contain SPOILERS, and are only recommended if you've already seen the movie. You can check my introduction to these breakdowns, to get an overview of my process and philosophy.

Feel free to let me know what you think in the comments below!

The Basics

Director: Steven Soderbergh

Writers: George Clayton Johnson & Jack Golden Russell (1960 story), Harry Brown and Charles Lederer (1960 screenplay), Ted Griffin (screenplay)

Release Date: 2001

Runtime: 116 Minutes

IMDB: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0240772/reference/

Movie Level Goals

Protagonist: Danny Ocean

External: Rob the Mirage, Bellagio, and MGM Grand

SUCCESS | FAILURE | MIXED

Internal Goal: Win back Tess

SUCCESS | FAILURE | MIXED

Goal Relationship: External Goal leads to Internal Goal

Three Observations

Observation #1: Romance Subplot

In many obvious ways Ocean’s 11 is a throwback to older films, from its focus on movie stars as the central attraction to its nostalgic portrayal of Las Vegas. Another old-fashioned aspect of the film is its romance subplot. Of course, many movies still feature a romance, and romantic comedies (which are slowly making a comeback) focus on the romance as the central plot line. But it has become increasingly rare for a movie to have a strong, external primary plot and a romantic secondary plot. I think there are a variety of reasons for this, but certainly stronger female characters is a main reason, as is the proliferation of comic-book and superhero movies with their relatively asexual heroes.

But given its throwback style, Ocean’s 11 sets up an old-fashioned Hollywood romance with Julia Roberts as Tess being the object of Danny Ocean’s desire. As usual, the external and internal goals are closely linked, with Danny’s internal goal* of winning over Tess (i.e. rob Terry of his girlfriend) being dependent on the successful completion of the external goal of robbing Terry Benedict’s three casinos.

*It’s worth explaining that while Danny’s pursuit of Tess seems relatively external (it primarily involves another person, rather than a strong focus on Danny’s internal need for love), it functions in a similar way to most internal goals. It provides meaning to the movie, rather than structure and is certainly the secondary goal. More often than not, romance subplots function in a similar way to internal goals, so even if they seem somewhat external, I tend to refer to them as internal goals. In this case, calling the romance subplot a secondary goal is probably more accurate.

Observation #2: Mass Protagonist

While Danny Ocean is clearly the protagonist of Ocean’s 11, the movie also clearly functions with a mass protagonist. Mass protagonists differ from multiple protagonists in that mass protagonists all have the same movie-level goal, and thus function structurally as a singular protagonist. Multiple protagonists each have their own, unique movie-level goal, thereby radically altering the structure of those movies. In Ocean’s 11, Danny Ocean and the 11 members of his crew, all share the same movie-level of robbing the three casinos. In any particular scene, individual characters may have distinct goals (such as Linus pretending to be a member of the Nevada Gaming Commission in order to gain access to the secure area of the casino), but at the end of the day, all characters share the same large scale goal.

Observation #3: No Conflict

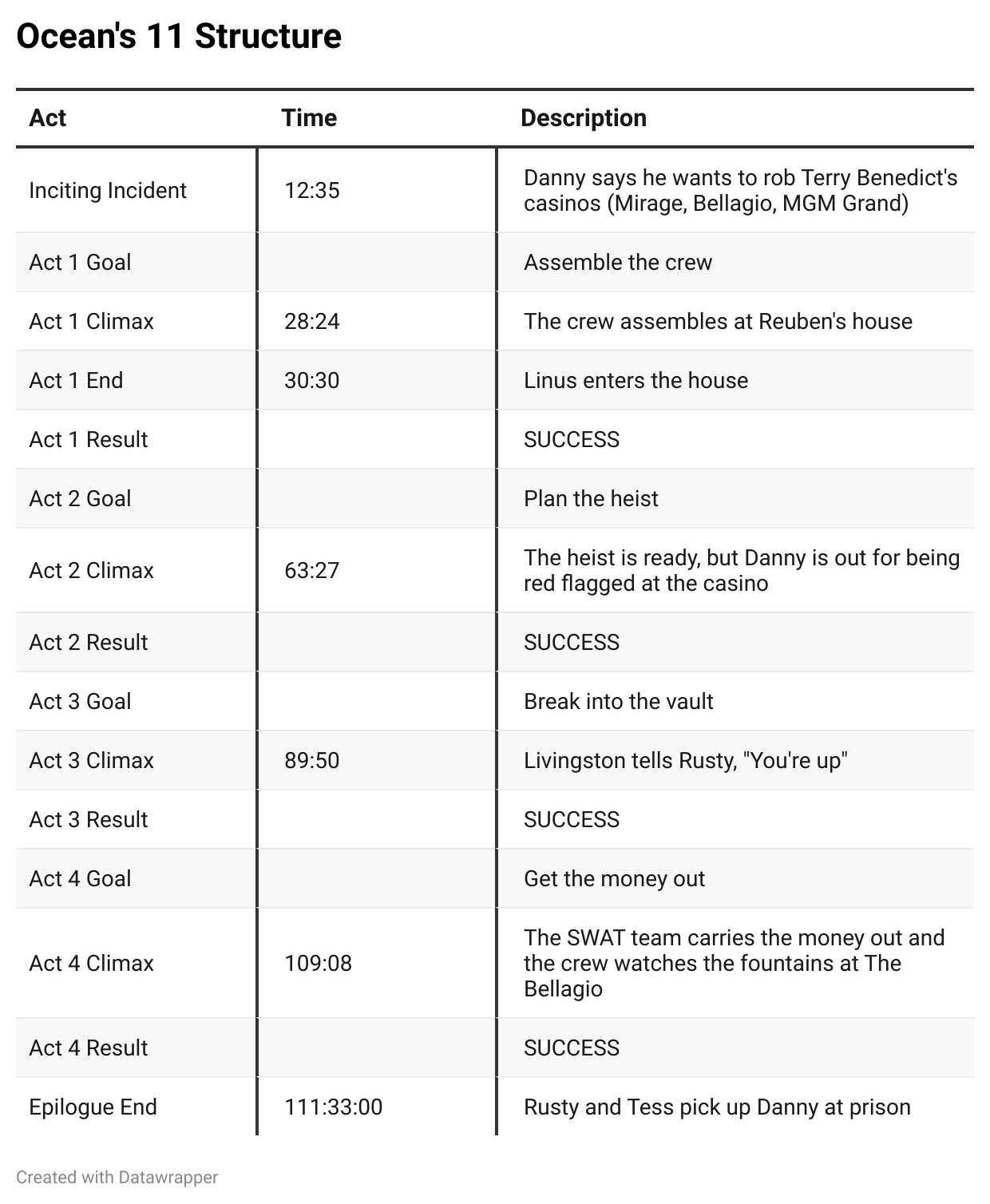

On the surface, Ocean’s 11 feels like a highly complicated movie. A closer look reveals that structurally (as the table shows) the movie is actually relatively simple. What makes it highly unique, however, is the movie’s lack of conflict. On the movie-level, in theory, Terry Benedict and the casino security provide the main conflict for Danny and the 11. But rarely does Terry, or any of the aspects of casino security, actually create conflict. Likewise, and perhaps even more importantly, most scenes don’t involve much conflict either. For example, Act 1 from roughly the 18-minute mark to the 28-minute mark, focuses on recruiting the members of the crew. But the conflicts during recruitment are almost non-existent. Basher must be freed from police custody and Danny briefly doubts Yen’s abilities. In other scenes, the conflict is between the recruited crew member and someone else (for example Livingston being upset that the FBI are playing with his equipment). But these are low-stakes conflicts that require little or no reaction. Likewise, in Act 2, the crew go through a series of preparatory actions with only a handful of conflicts–Rusty discovering Tess is involved, Basham having to find a new way to cut power, Linus getting left behind during the robbing of the “pinch” and Danny being red-flagged. And again, the reactions are relatively minor–Rusty gets briefly upset with Danny, Basham comes up with stealing the “pinch”, the crew go back for Linus, and Danny ignores his ban and joins the heist. In Acts 3 and 4, the heist (getting into the vault and getting the money out) goes off almost without a hitch (Yen’s bandaged hand getting stuck is one exception).

So how is the movie so successful given that it’s missing what we generally consider to be a key component of compelling dramatic structure? We can find the answer in Robert McKee’s compelling definition of conflict. In his famed screenwriting book Story, he defines conflict as a, “gap between expectation and reality.” Danny and the rest of the crew rarely experience a gap. What they expect to happen (the various steps in executing the heist) generally matches the reality of what does happen. But there is a gap that constantly exists, and that is between the audience’s expectations and reality. Danny and the crew are always one or more steps ahead of us. They know the plan and what is supposed to happen. We, the audience, do not. So we are constantly surprised by the events of the movie and how the crew execute the various steps of the heist. The gap exists for us, and the pleasure of the movie comes in the ways the movie constantly surprises us in filling those gaps.