Mission: Impossible

So with my colleagues Daniel and Donavon officially launching the rebrand of their podcast from 241 to Reel Therapy AND the release of what may be the final Mission: Impossible movie (MI:8 The Final Reckoning), this seemed like the perfect opportunity to go back and revisit the original Mission: Impossible film from 1996, directed by the incomparable Brian de Palma . While it’s known for some great suspense and action scene, including the Tom Cruise dangling from the ceiling of the CIA HQ computer room, the movie is actually filled with some really interesting narrative and structural moments. So please read on, and listen to or watch the first edition of Reel Therapy (formerly 241)—and no, this post will NOT self-destruct five seconds after you’re done reading it!

As always, these breakdowns contain SPOILERS, and are only recommended if you've already seen the movie. You can check my introduction to these breakdowns, to get an overview of my process and philosophy.

Feel free to let me know what you think in the comments below!

The Basics

Director: Brian DePalma

Writers: Bruce Geller (Original TV Show), David Koepp, Steven Zaillian

Release Date: 1996

Runtime: 110 Minutes

IMDB: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0117060

Movie Level Goals

Protagonist: Ethan Hunt

External: To prove his innocence and reveal the mole

SUCCESS | FAILURE | MIXED

Internal: None

SUCCESS | FAILURE | MIXED

Three Observations

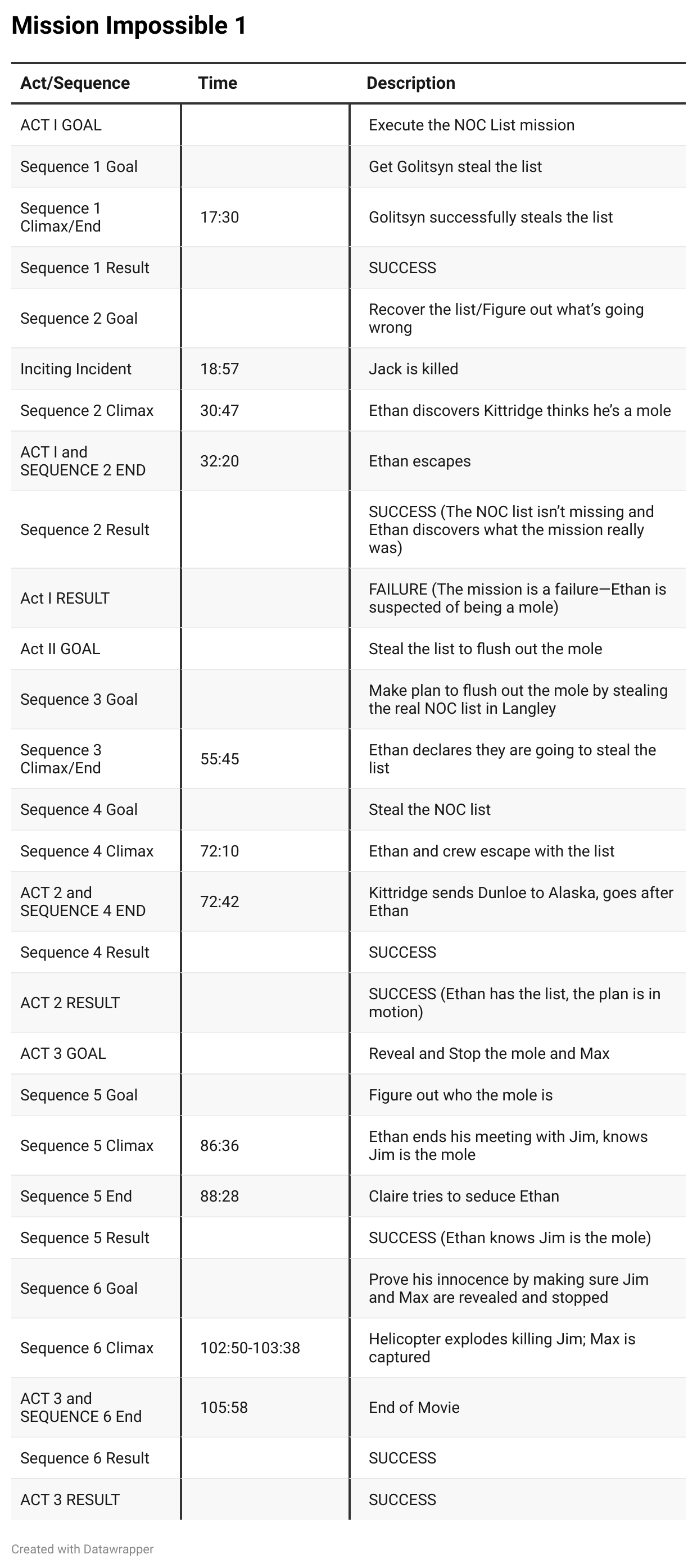

Observation #1: Three Acts/Six Sequences

The first thing that stands out about Mission: Impossible Is it three-act, six-sequence structure. It's not the most unusual structure you'll find but it is relatively uncommon. First, more often than not, Hollywood movies will either be structured as acts or sequences. Acts allow for a slightly looser cause-and-effect chain and more sub plots. Sequences, on the other hand, allow for tighter cause-and-effect chains and a tighter focus on the plot line of the protagonist. Having said that, there are plenty of movies in which we can find sequence goals embedded in acts. When I have encountered this kind of structure, it tends to be a four-act structure with either eight or 12 sequences (that is either two or three sequences per act). For example, the Pixar movie The Incredibles, has a four-act 12-sequence structure that is very exact. I think Mission: Impossible has both acts and sequences, because it is really splitting the difference between what act structure and sequence structures do. In particular, sequence structures are most often found in action oriented movies in which we often move from one set piece to the other with very few breaks. Despite the reputation of the Mission: Impossible series as a whole, the first Mission: Impossible actually has very few clearcut action scenes or sequences. Instead, the film is often based around mystery and suspense. If you look at the sequence listed in the table above, you'll find that most of them are either built around suspenseful goals or investigative goals, rather than action goals. The two main action goals can be found in sequence four, in which Ethan attempts to steal the NOC list, and sequence six in which Ethan tries to prove his innocence and stop Jim and Max from executing their plan. Sequences one and two have some action, but are built primarily around suspense (especially sequence two in which Ethan tries to figure out what's going wrong with their plan). Sequence three is primarily built around planning the theft of the NOC list, and sequence five is built around Ethan confirming that Jim is indeed the actual mole. As we know about the Mission: Impossible series, and many other action oriented franchises, movies seem to have gotten longer and longer. With the first Mission: Impossible being released in 1996, we find a shorter and tighter movie. At 106 minutes before the end credits, it makes sense that the movie is three acts rather than four acts. If this movie had been made 10 years later, it would most likely have been four acts, and if it had been made 20 years later it might have even had five acts.

Observation #2: Sequence Two Inciting Incident

Even more unusual than the three-act six-sequence structure, is the placement of the inciting incident. Even when a movie is built around an act structure rather than a sequence structure, it is not uncommon for Act One to feel like it is built around two sequences, and that is because of the inciting incident. Inciting incidents can occur anywhere in Act One from the very first minute all the way to the act climax. However, it is most common for inciting incidents to fall somewhere in the middle of the act, often around the 15-minute mark (Syd Field famously declared that inciting incidents should happen at minute 17). Whether it's the 15-minute mark or the 17-minute mark, if an act is typically around 30 minutes, it makes sense for the inciting incident to occur roughly in the middle. This allows the first half of the act to focus on exposition and character development, as well as setting up the status quo of the protagonist. Once the inciting incident happens, the protagonist either immediately forms a goal which they pursue for the rest of Act One, or they spend the rest of Act One trying to decide whether or not to respond at all or trying to figure out what to do. Because the inciting incident falls in the middle of the act, and because a shortened Act One goal often follows the inciting incident, Act One often looks like it is structured with two sequences (and one could argue that there are two sequences in many first acts). In the set up, the inciting incident basically acts as the climax of the first sequence of Act One. What's interesting about Mission: Impossible, is that the inciting incident happens at the beginning of the second sequence of Act One. The first sequence of Act One starts with the goal of allowing Golitsyn to steal the NOC list. This is actually the status quo for the characters and there really hasn't been an inciting incident up until this point. At the 17 1/2 minute mark, Golitsyn successfully steals the list and the sequence one goal climaxes and seems to be successful. The team must still capture Golitsyn and make sure the list isn't released into the wild, but this seems to be treated as a forgone conclusion by the team. Instead, as Golitsyn leaves with the list and the team follows him, we have a surprising event in the death of the team member Jack (played by Emilio Estevez). This inciting incident happens around the 19 minute mark, and is what changes the status quo for Ethan, as well as setting up the goal for sequence two which is to try to recover the list as he also tries to figure out what's going wrong. While the inciting incident still falls roughly in the middle of the act, especially since the act runs about 32 minutes, placing the inciting incident at the beginning of sequence two rather than the end of sequence one creates surprise for the audience by killing Jack just when we thought the mission had been successful.

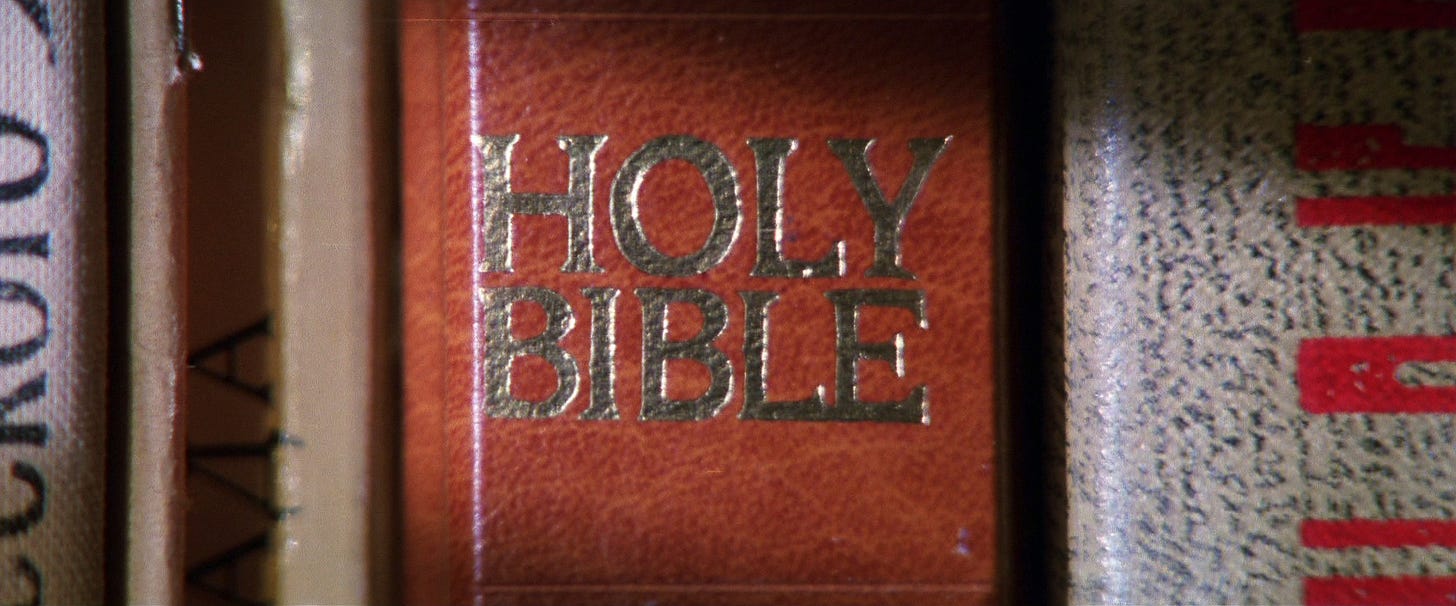

Observation #3: The Bible Reveals the Answers

I think the most interesting and unusual aspect of Mission: Impossible is the structure of sequence five. At the end of sequence four, Ethan and his team has have successfully stolen the NOC list. At the beginning of sequence five, the team goes to London and Ethan has a run-in with Krieger who threatens him because he has the NOC list. Ethan bluffs his way out of the situation making Krieger think he doesn't possess the NOC list and manages to get the list away from him. After this tense encounter with Krieger, Ethan sit down at the laptop and notices the Bible sitting on the shelf that he had used earlier to contact Max. He pulls the Bible from the shelf, opens it and sees that it is stamped as being from the Drake hotel in Chicago. At the same time, we hear a voiceover in which Jim admits to staying at the Drake hotel in the same city. Putting 2+2 together, it seems pretty clear that Jim must have used the Bible to communicate with Max, and is therefore the traitor and the mole. I think this is both clear for Ethan and for any audience member who has been paying attention. What's fascinating, is that the goal for the sequence seems to be to figure out who the mole is, but Ethan has done so roughly 3 1/2 minutes into the sequence! How can an entire sequence be built around a goal that is resolved in the first three minutes? I think there are two answers here. The first, is that Ethan wants confirmation that Jim is the mole—after all, as far as Ethan knows, Jim is dead. And second, he wants to work out what Jim's plan is and how he sabotaged the mission in the first and second sequences. At the 79-minute mark, about seven minutes into the sequence, Ethan goes to the train station to call Kittridge, and discovers that Jim is there and is alive. Ethan and Jim sit down in a café, and Jim narrates to Ethan his experience of what went wrong that night, and tries to convince Ethan that Kittridge is the mole. In an extremely clever bit of filmmaking, as Jim narrates his version of events, Ethan visualizes the true version of events with Jim as the mole and saboteur. Jim's narration actually helps Ethan fit the pieces of the puzzle together and understand what must have actually happened. So while he seems to know the identity of the mole for the entire sequence, by the end of the sequence, Ethan has confirmed that Jim is alive and is the mole, and has figured out how he sabotaged the mission. Of course, Ethan doesn't reveal this information, and plays along with Jim heading into the final sequence. He does this for a number of reasons including the fact that he is not sure whether Claire is part of Jim's plan, and because he wants to make sure that Kittridge witnesses the truth for himself, which will clear Ethan as the mole.

Observation #4: It’s okay to be successful

My short, final observation is about a commonly misconceived belief about the success or failure of goals. Most screenwriting “gurus" insist that protagonist must face failure or at some point reach rock-bottom. While this is often the case, and can increase the stakes and drama of the story, it is certainly not necessary for a movie to be compelling. Mission: Impossible is a perfect example. If you look at the chart above, you'll notice that for each of the six sequences, Ethan successfully completes every single goal. When you look at the goals for the three acts, it is true that despite being successful in both sequence one and sequence too, Ethan does fail at his act one goal. However, it's clear that Ethan is largely successful in almost everything he sets out to do. While I think this is due to the fact that Ethan is Ethan, and we expect him to be successful, it doesn't mean that we still don't have suspense and high stakes throughout the movie. One might argue that confirming Jim is the traitor at the end of sequence five marks a low point for Ethan, but he is already two steps ahead, and is planning how to take down Jim in the final sequence. I think the larger takeaway here is that there is no formula for how to climax sequences or acts. Protagonist may or may not succeed at their goals, but each movie and plot has its own needs for whether the protagonist succeeds or fails at those goals, and there is no one right way to handle those climaxes.