An Appreciation of Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’avventura

Back in June I was invited by UCAFilm alum Kris Pistole to be a guest on his Podcast Classic Cinema Society. Pistole asked me to choose a film for discussion, with the main limitation that it be a classic film from before 1970. I asked if we could discuss a foreign film, and he was excited about the possibility since they had not featured a foreign film on the podcast at that point. I suggested one of my all-time favorite movies, Michelangelo Antonio’s L'avventura, and Pistole agreed. This week Pistole posted the podcast, which you can listen to on YouTube or using your regular podcast app.

We had a fantastic discussion, so I decided to write up an accompanying appreciation and breakdown of the film. Since this is both an appreciation and a breakdown, you'll find a lengthy discussion first and then my act breakdown of the film at the end.

As always, these post contain SPOILERS, and are only recommended if you've already seen the movie.

Feel free to let me know what you think in the comments below!

The Sight and Sound Poll

Tracking L'avventura's standing in the pantheon of cinema is an interesting exercise. The movie premiered at the Cannes film festival in 1960 and was initially greeted with a sustained round of booing. Yet at the end of the festival, the film received a special jury prize for "the beauty of its images, and for seeking to create a new film language.”

This regard for the film was reflected just two years later in Sight and Sound’s 1962 poll of the greatest films in cinema history. Astoundingly, L'avventura ranked second in the poll that year. In 1972, the movie slipped to number five and in 1982 the movie slipped two more places to number seven, though had obviously remained in the top 10. In 1992, the film slid 10 spots to number 17 followed by a five spot slide in 2002 two number 22, and then a one spot rise in 2012 to number 21. The real shocker occurred in 2022 when the film tumbled 51 places and landed at the 72nd overall spot in the poll.

Of course, there's no real way to know why exactly the film fell so far. I believe voting was open to a much larger number of people, and when you look at the 2022 poll you will see a lot of recent films that were added to the poll. However, I'll also offer one or two other possibilities later in my discussion.

“A New Film Language?”

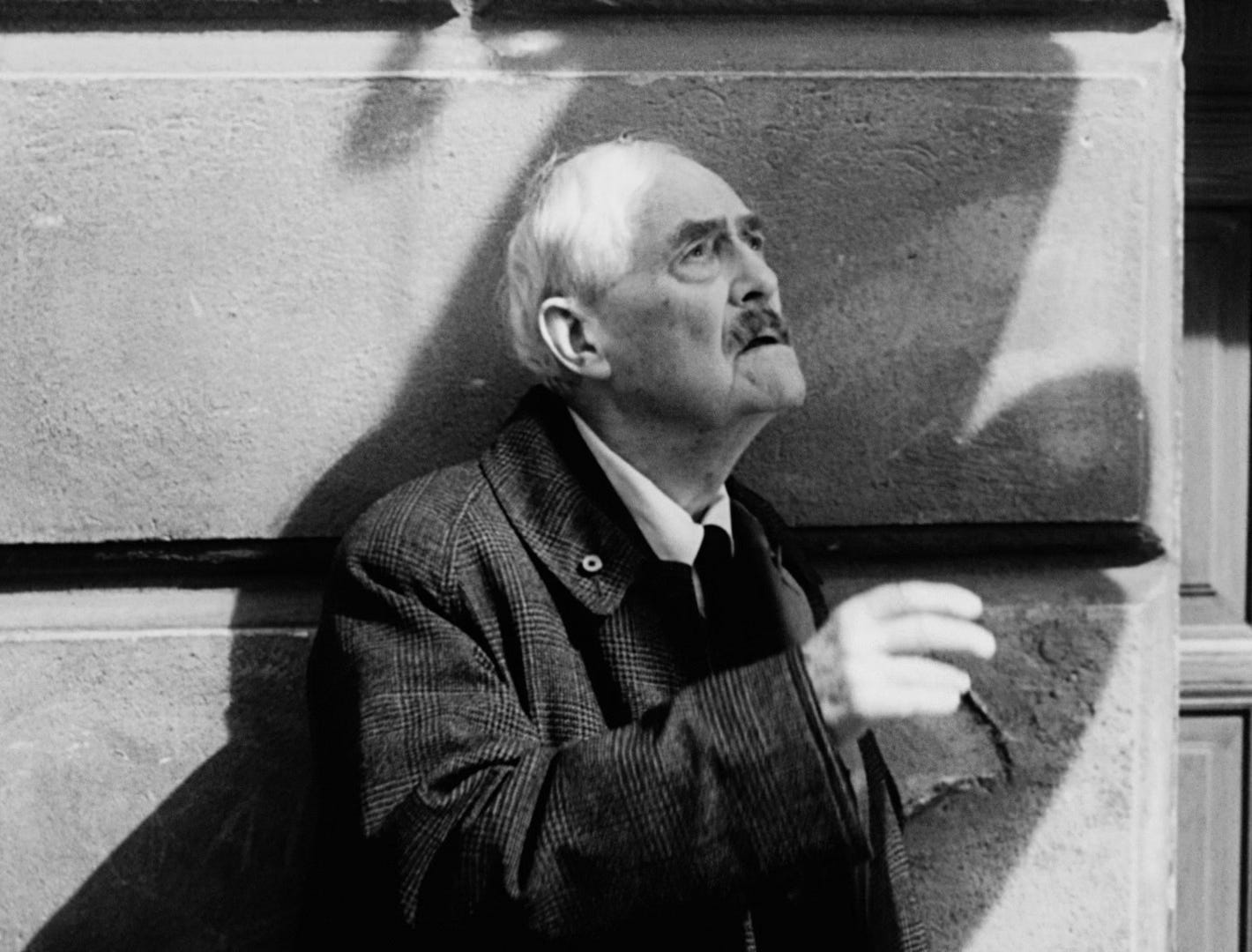

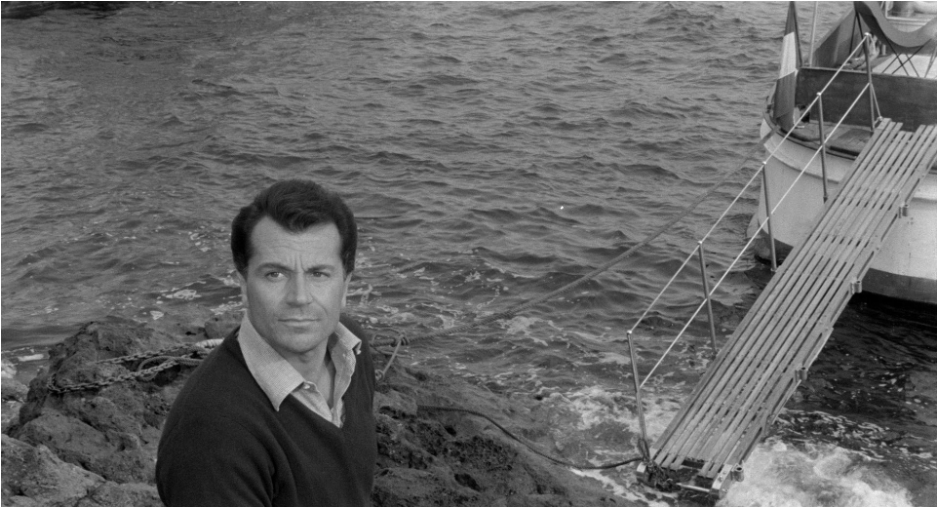

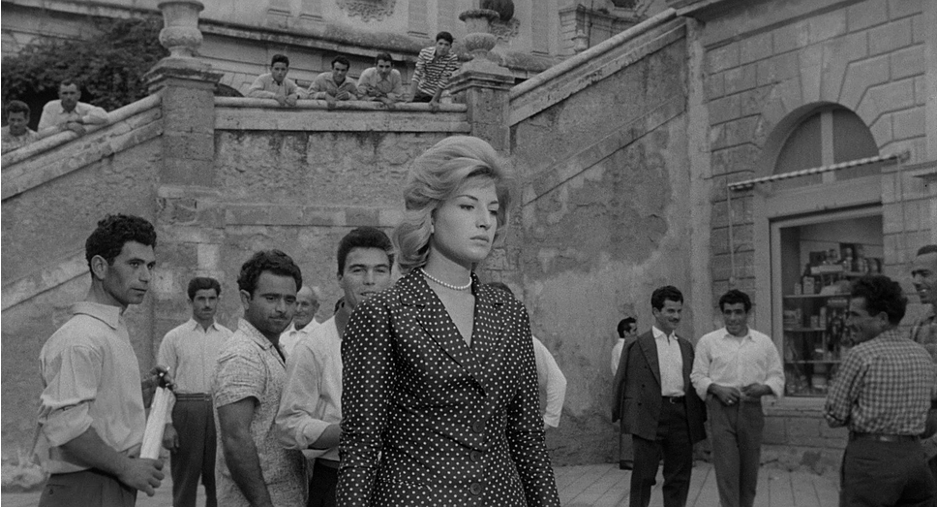

As I noted above, the jury at the 1960 Cannes Film Festival gave the film a prize for both “…the beauty of its images" and "for seeking to create a new film language.” I think the first half of the quote is fairly straightforward, and the stills I've included illustrate this well. Additionally, I'll talk a little bit more below about the specific aspects of composition that stand out in L’avventura.

But what does "a new film language” mean? Clearly the jury felt that L'avventura had done something new, something that had not been seen in cinema before. But often times when people use the phrase "film language" they often mean the combination of visuals and storytelling. That is true here, but I think we need to dig a little deeper.

I think what was extraordinary and new about what Antonioni was doing with L'avventura was his refusal to provide clear, external motivations for the actions of his characters. The film has three main characters: Anna, her boyfriend Sandro, and her best friend Claudia. Anna is clearly experiencing a psychological, emotional, spiritual, and existential crisis in the first act of the movie. What's unclear, is why exactly she is experiencing this crisis. After Anna disappears, Sandro and Claudia team up to try to find her, but slowly abandon their search and instead begin a romantic relationship of their own. While this relationship might seem to be in poor taste, Sandro barely questions it, though Claudia does seem more troubled. As with Sandro, the rest of their friends make little or no note of how quickly they move on from Anna. Why do Sandra and Claudia behave in this way? As the film progresses, both revel in their romance, but also seem to be uneasy, with Sandro eventually cheating on Claudia and Claudia struggling to balance her newfound happiness with a deeper sense of dread and unhappiness. Again, what is going on with these characters and why are they making the choices they do and experiencing the emotions they feel?

What made L'avventura so radical in 1960, is that none of the characters attempt or are able to explain their motivations or feelings. We simply watch them make the choices that they make, and are left to figure out for ourselves what is going on internally for each of them. Most movies before L'avventura, and even most movies since, tend to externalize the internal. That is, through dialogue and action, we generally have a strong and clear sense of character motivation. However, instead of relying on dialogue and action as the primary drivers of motivation, Antonioni instead relies on context, shooting style, composition, acting, and other much more subtle cues to externalize the internal. In 1960, I think this was a new and foreign form of filmmaking, and caused audiences to struggle with the movie, but also caused critics to understand that it was attempting something new.

To contextualize this, we can look at some of the other great auteurist films that were released around this time. Perhaps the greatest auteur of the 1950s was the Swedish director Ingmar Bergman. In 1957, he released both the Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries. These are both considered classics of modernist cinema, yet they are both easily understood, with characters whose motivations are quite clear. Additionally, Bergman uses very specific devices to aid in externalizing the internal feelings of his protagonists. For example, the Knight in the Seventh Seal is afraid of death. Not only does the Knight express those fears through dialogue and action, he literally plays chess with the Grim Reaper to try to stave off death.

Likewise, Professor Borg in Wild Strawberries travels to the university he graduated from in order to receive an honorary degree to to recognize his life's work. As he makes the drive, he encounters a series of characters as well as stopping at the family home of his youth. While the Professor is less inclined to discuss his feelings than the Knight in the Seventh Seal, Bergman uses a series of flashbacks and dreams to externalize the internal feelings of Professor Borg. Through these we discover his past history, his dreams, and his regrets. In both cases, the films externalize the internal lives of the characters in ways that make them easier to understand for the audience.

Other films that played at the film festival in 1959 and 1960, or came out around the same time, include François Truffaut’s 400 Blows, Jean-Luc Goddard's Breathless, La Dolce Vita by Federico Fellini, and Hiroshima mon Amour by Alain Resnais (what an amazing time in cinema history!). In all of these films, the motivations of the characters are generally relatively clear. The exception might be Patricia in Breathless, whose motivation for turning in Michel is mysterious (but even this happens at the very end of the movie). Additionally, while Hiroshima mon Amor beautifully experiments with time, the actual motivation of it two romantic leads are relatively straightforward. Contrast this with Antonioni's L’avventura, and we can see how his reliance on context, shot composition, and other more subtle clues to create character motivation would have been seen as both challenging for audiences and as" creating a new cinematic language.”

So why has the film fallen so far in the Sight and Sound poll in the last 10 years? I think the answers are somewhat contradictory. First, since the release of L'avventura in 1960 there have been many more art cinema films that have replicated Antonioni's enigmatic approach to character. For example, Andrey Tarkovsky's later works, including Nostalghia written by L'avventura's screenwriter Tonio Guerra, features characters and scenes whose motivations are obscure. So in a way, viewers well-versed in cinema history may have grown used to the “new film language” of Antonioni. Second, and contradictorily, while films of this nature are more common, they are still difficult to watch and perhaps have become less popular in a social media age where films tend to be very obvious and clear in their themes and motivations. Along these lines, L'avventura may suffer in comparison to equally great, but less subtle and more obviously groundbreaking films. For example, Antonioni's compatriot Federico Fellini's kaleidoscopic masterpiece 8 1/2 ranks at number 31. And even the number one film, Chantal Ackerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, while difficult to watch at four hours long, is clear in it's groundbreaking use of the slow cinema techniques of a fixed camera and long takes. Finally, I’ll note that much of the thematic focus and conflict for the characters of L’avventura is existential. At the moment, I think existential themes are less popular than more overt political and sociological themes (Get Out is already on the poll at #95).

Intellectual or Emotional

This enigmatic approach to character motivation, and the refusal to externalize the internal has led some to see L’avventura (and other Antonioni films) as more intellectual than emotional. This view is enhanced by Antonioni’s great Italian colleague Federico Fellini who generally externalized everything about his characters and themes. Personally, however, I find L’avventura (and Antonioni’s other films ) to be incredibly emotionally moving. The charge of intellectualism (which by the way is not a bad thing in and of itself) I think stems from the fact that the characters don’t often directly express emotion and that audiences therefore have to “work” at figuring them out, which seems to make these movies seem intellectual.

But for me, there is perhaps nothing more human than hiding emotion, being afraid to express oneself, and struggling to figure out why you feel anxiety, depression, dread, fear and alienated from the people and world around you. In fact, the struggles of Anna, Sandro, and especially Claudia, could not be more relevant to where many of us find ourselves emotionally in today’s social media, post-truth, politically retrograde world. We are somehow more connected, yet more alienated from each other than we have ever been. The struggle to identify these feelings, understand them, and learn to live with them, is incredibly emotional, and that struggle is beautifully embodied by the fantastic actress Monica Vitti. While Anna is the only character who gives any sort of voice to her alienation and existential struggles, it is Claudia who is the main focus of the audience’s understanding of them. While she is slow to recognize them, her increasing sense of loss (and lostness) becomes the centerpiece of the film. She wants to feel grief, but is afraid of it. She wants to feel love, but is unsure of what it looks like. She wants to be happy, but doesn’t know what true happiness is. Throughout this struggle Claudia, and all of the other characters primarily look inward, and none of them seem able to experience any true emotion.

These struggles are subtlety and cleverly communicated through the constant repetition of one word—“Why” (Perchè)? Repetitions and variations of the word occur throughout the film, and in key scenes. In fact, each of our three main characters repeats this question. Anna most famously near the beginning of the film when she makes love to Sandro, Sandro later when he is discussing his choice to quite architecture and his desire to return to it, and Claudia in response to Sandro’s own “Why.” When she tells him to say he loves her, he asks “why?” And she repeats the question, seemingly in a moment of self-reflection. Why should Sandro say he loves her? In fact, L’avventura uses the word “Why”/“Perchè” a total of 73 times. Just to compare to some of the previous mentioned classics mentioned above, the word “why” appears:

• 11 times in The 400 Blows

• 15 times in Hiroshima mon Amour

• 19 times in Wild Strawberries

• 27 times in La Dolce Vita

• 31 times in The Seventh Seal

Or to put it another way, the word “why” appears every two minutes in the film.

The breakthrough for Claudia comes at the movie’s bittersweet ending. Finding themselves unexpectedly reunited with some of their wealthy friends at a hotel, Claudia and Sandro have differing reactions. Claudia, perhaps ashamed of giving up the search for Anna and beginning to feel both loss and lost, prefers to go to bed early and not face her acquaintances. Sandro, barely in touch with his existential struggles, is happy to go socialize (it should be noted, though, that even Sandro struggles, primarily through his barely expressed regrets at giving up architecture and the creative life for the easy and financially rewarding life of providing estimates for building projects). Claudia, however, is unable to asleep and craves Sandro’s company, so in a panic searches the hotel through the early morning hours after most of the revelers have finally retired for the night. Finally, she finds Sandro in the arms of Gloria Perkins, the American “It Girl” (and prostitute), and runs off in tears. She and Sandro find themselves reunited at dawn, with Sandro sitting in tears on a bench looking out at Mount Etna, unable to explain his actions. Finally, in perhaps the movie’s first true act of humanity and connection, Claudia, hurt and shamed by Sandro’s actions, reaches out and caresses the back of his head, acknowledging his pain and confusion, and perhaps finding an answer to her own existential alienation: compassion for the pain of others.

The Compositions

As mentioned above the Cannes Jury also recognized the “beauty of [L’avventura’s] images.” The black and white cinematography by Aldo Scarvara is beautiful, as are the Sicilian locations. But the movie is also full of original and arresting compositions including:

Unbalanced Frames (both horizontal and vertical):

Characters With Their Backs to the Camera:

Mixing Depth and Flat Framing:

The Use of Mise-en-Scene to Create Meaning:

Structure

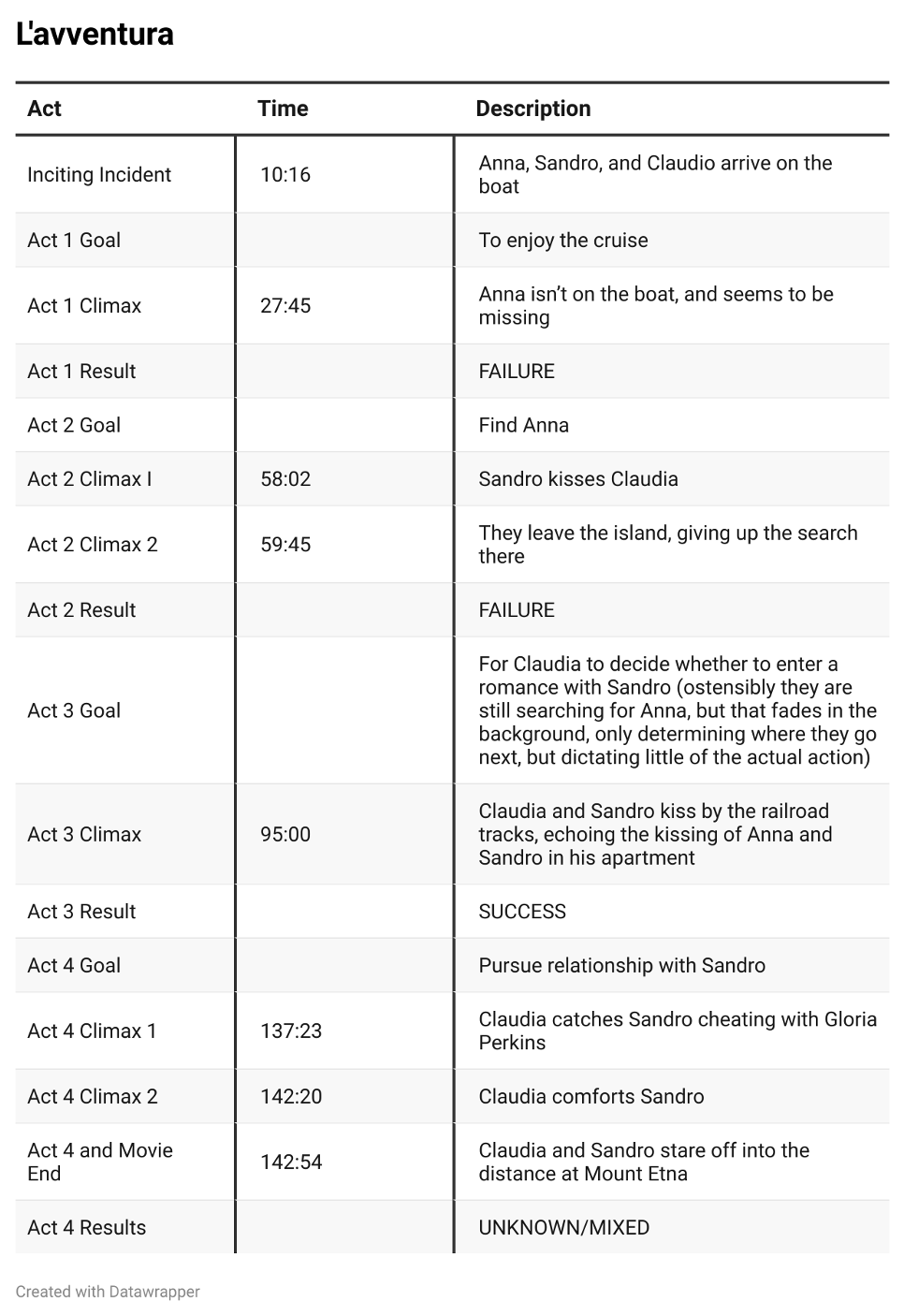

Much of my work, especially on this blog, is an examination and analysis of the narrative structure of films based around sequences or acts defined by character goals. Usually, my assumption is that structured narratives are most common in Hollywood films of the past 50 years or what the writer Robert McKee has labelled arch-plots. Mini-plots, which focus less on the external goals of characters, tend not be as structured, and therefore an examination based on sequences or acts is less relevant (and is often the case with art and independent cinema). However, lately, I’ve been finding structure even in movies that on the surface seem less structured, including older films and mini-plot style art cinema and independent films. While perhaps not a conscious choice by the filmmakers, it might be that seeking or creating structure in narrative is more common than it seems, perhaps making it easier for both filmmakers and audiences to navigate even tricky, challenging cinema (though I want to be clear I’m not making a claim that all films contain structure). And after watching L’avventura for my discussion with Pistole, I discovered it has a fairly straightforward act structure.

So below you’ll find my abbreviated structure breakdown of L’avventura. Given how much I’ve written above, you won’t find my normal “Three Observations”, but I’ve listed goals and times below, and you can decide whether or not you agree with my findings.

The Basics

Director: Michelangelo Antonioni

Writers: Story by Michelangelo Antonioni, Screenplay by Michelangelo Antonioni, Elio Bartolini, and Tonino Guerra

Release Date: 1960

Runtime: 144 Minutes

IMDB: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0053619/fullcredits/?ref_=tt_cst_sm

Movie Level Goals

Protagonist: Claudia

External: Find love (with Sandro)

SUCCESS | FAILURE | MIXED

Sandro cheats on Claudia, but her kindness in the movie’s final shots makes their future unclear

Internal: To figure out her existential crisis

SUCCESS | FAILURE | MIXED

Again, Claudia’s compassion for Sandro at the end of the movie hints at a path forward to moving out of her sense of alienation and existential dread